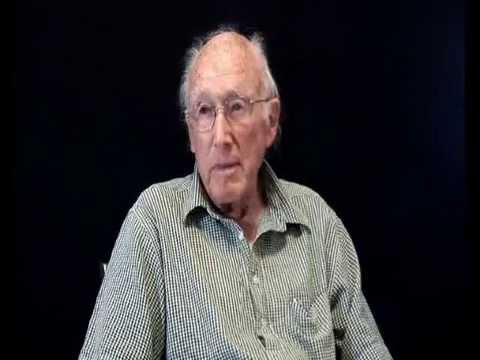

Keith Sellar

Keith Sellar

“The Portites were pure gold”

Keith was born on 12 March 1929, and grew up in the Port. One of his first memories was the Napier earthquake, when he was only two years old. From his house part way up the hill, he saw bricks from his collapsing chimney cascading downwards. “None hit me…well, some (people) think one brick must have hit me on the head!” he jokes. The house ended up burning down, and like many families in the area, he went to live with family elsewhere for a while. He later lived on Waghorne and Outram Streets in the Port.

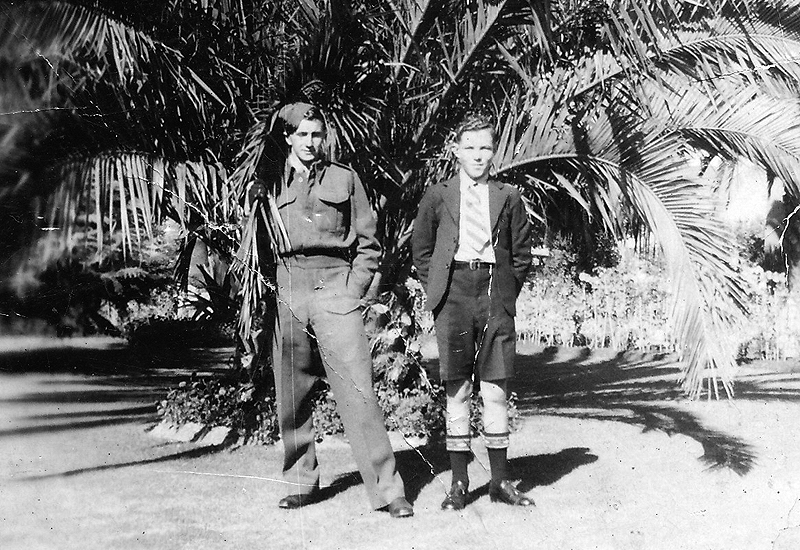

Keith attended the Port School, then did several years at Napier High School before completing an Electrician apprenticeship and working six years in the trade. He then decided to undertake tertiary studies in the form of seminary training at Knox College – Otago University, Dunedin. After graduating and marrying, Keith worked in the Presbyterian Church, then after leaving the ministry, did social work in the community at the Port.

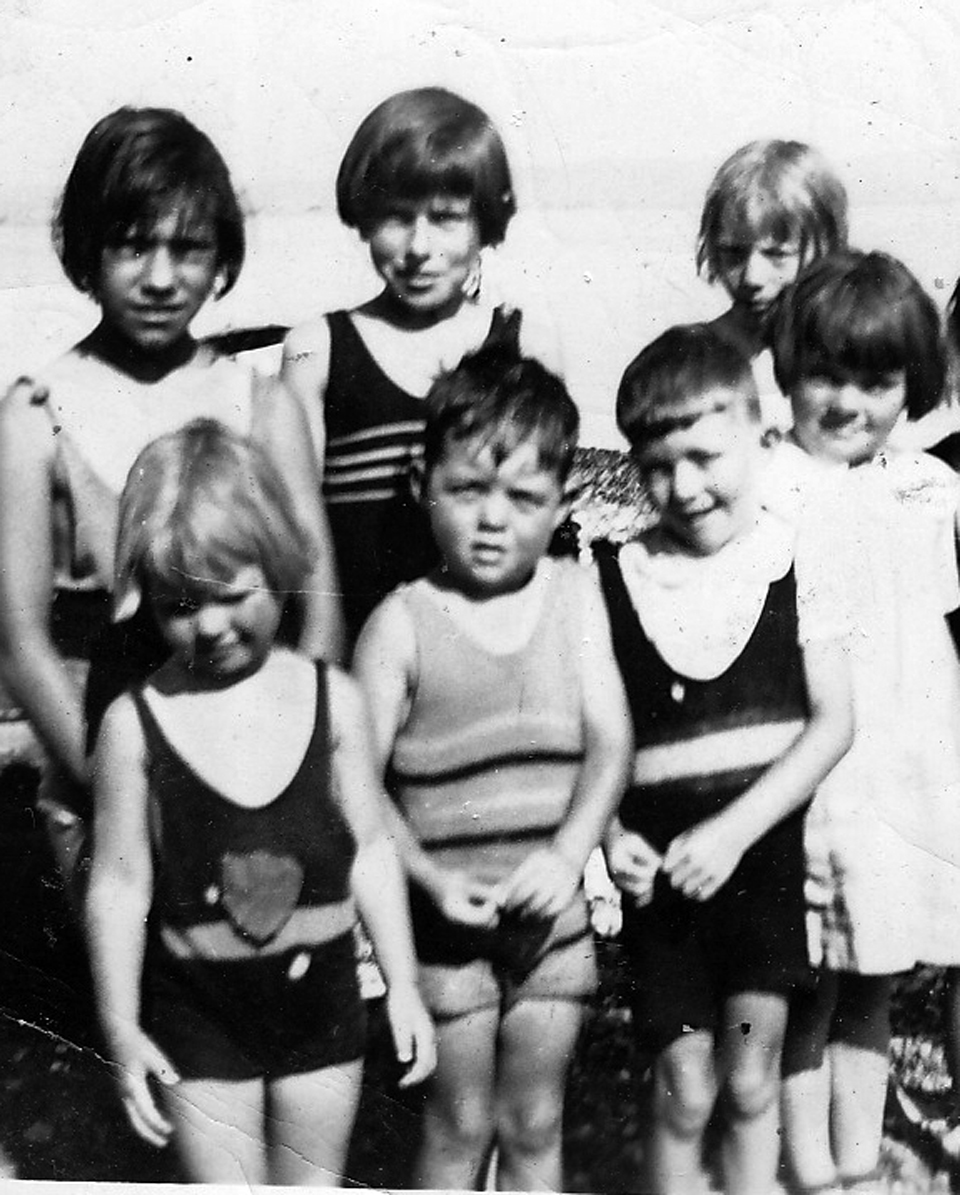

Of his growing up, he remembers the fraternity, playing with other kids at the beach, and searching under rocks for crab and fish at low tide. He had a paper round working for Mr McCarthy who owned the book shop, and used to take pleasure in shouting his parents and brother a treat in town on Christmas Eve with the money he had saved during the year. He also remembers building bonfires on Guy Fawkes.

Keith was sensitive in his youth to the financial difficulties of some families at the Port, especially during the Depression or outside of when there was seasonal work available at the wool stores, wharves or other businesses. His parents would give morning tea to men doing strenuous manual labour on government work schemes nearby, and Keith credits seeing the poverty around him growing up as helping him recognize the need for social work and assistance in the community – a path he would later pursue himself. An example Keith remembers of support the Portites gave each other was during winter: The wharfies would purposely over-fill the rail coal cars when unloading the ships, so that some fall over the sides when the carriages shunted-together. The local kids would then collect it to take home. When boats were not in, local firm Nivens would sell coal cheaply by the bucket-load to help the families. Mr Husheer, the owner of National Tobacco would send over an urn of hot cocoa to the Port School every day which the kids appreciated, and would hand out pennies to kids who looked like they needed it on Sundays. Keith rues the fact that attending Sunday School every week and thus being dressed in his ‘Sunday Best’ – Mr Husheer would often wrongly assume his family didn’t need the money and pass him over, giving money to the other kids who he thought must need it more.

Growing up, Keith sensed that the rest of Napier looked down on the Port as a result of their poverty, though many of the Portites didn’t consciously feel this as they didn’t leave the Port or associate widely outside it as Keith did with his part-time job. Within the Port though, he recalls the strong fellowship and feeling of community that almost everyone who grew up there remembers, and he “wouldn’t have wanted to grow up anywhere else “- another sentiment widely shared by the Portites. During the war years the Port’s financial fortunes improved with the wharfies and wool store workers picking up much overtime (at triple-time on Sundays!). Keith remembers a minesweeper coming to the Port to undergo engineering works at Nivens, and being able to go out on it with other boys on its subsequent sea-trials.

Related Images

Jim Blundell – War Joining up Into camp

Jim Blundell – War Joining up Into camp

Jim Blundell – War Joining up Into camp Jim Blundell – Provincialism and condescension

Jim Blundell – Provincialism and condescension Jim Blundell – Merchant Navy

Jim Blundell – Merchant Navy Jim Blundell – Home guard and Manpower work

Jim Blundell – Home guard and Manpower work Jim Blundell – Hard men combined

Jim Blundell – Hard men combined Alan Goss – Hardtimes Earthquake

Alan Goss – Hardtimes Earthquake Alan Goss – Entertainment at the Port

Alan Goss – Entertainment at the Port Alan Goss – The Port People Shaped life

Alan Goss – The Port People Shaped life Alan Goss – Intro Family Growing up

Alan Goss – Intro Family Growing up Audrey Bailey – Lagoon School

Audrey Bailey – Lagoon School Audrey Bailey – Local characters

Audrey Bailey – Local characters Audrey Bailey – The Port How its changed

Audrey Bailey – The Port How its changed